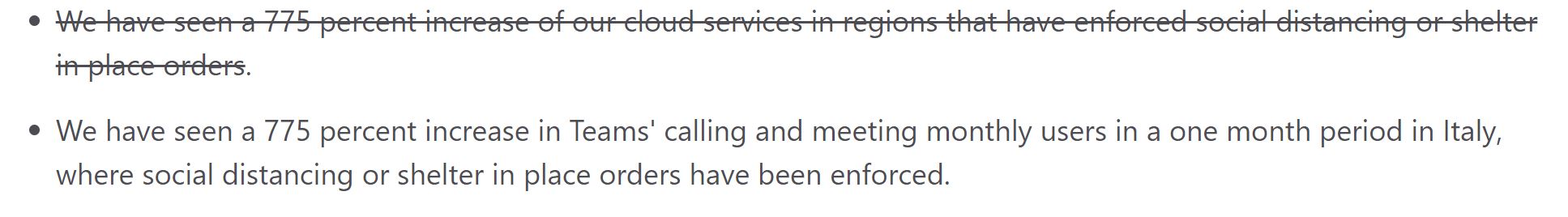

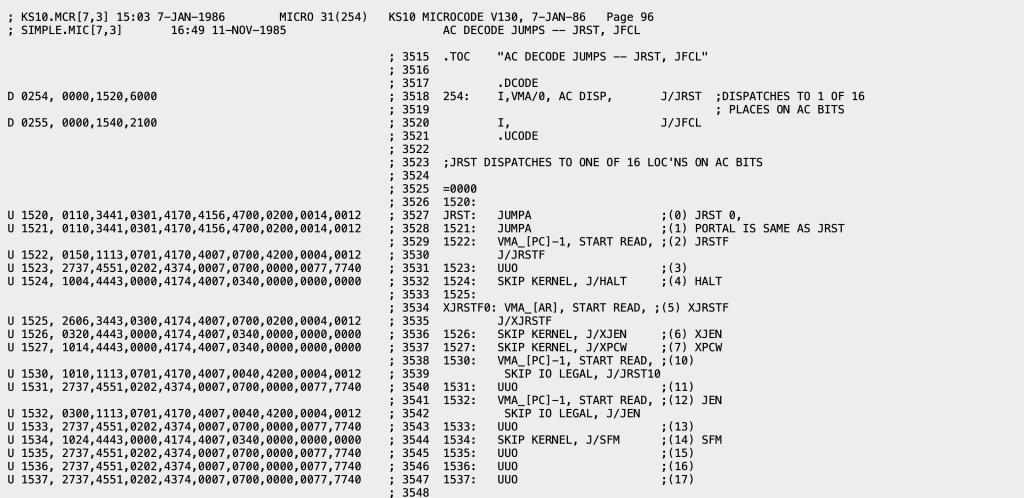

I’ve been thinking about this post for a long time, but using it to kick off 2026 just seems super appropriate. I have an unusually high percentage of readers who do know how to program a computer, but most of you don’t. You’ve never written a device driver. Fewer still in machine language. Speaking of machine language, you never wrote something (outside of perhaps a school project) in assembly language. You don’t know how to write code that lives in kernel space, and how to manage the transitions. And manually scheduling instructions for a RISC microprocessor? Nope, you haven’t done it. In reality, 98% of the developers of the world don’t even know what I’m talking about. Or how about this? How many developers even know what this is?

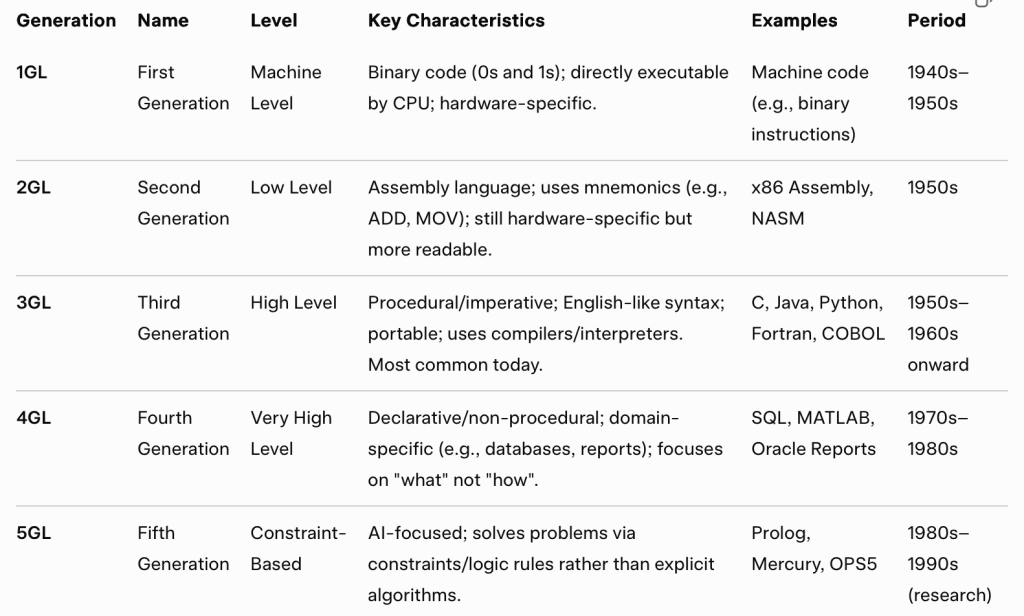

I’m not trying to pick on developers, I’m trying to make the point that from the earliest days of computing we’ve been adding abstractions to make it easier for developers to focus on solving a problem not manipulating the computer directly. By the 1970s, programming was moving up the abstraction stack in a big way. Some of that is reflected in the progress we were making in programming languages.

It wasn’t just the languages changing, it was the run-time libraries. We came into the 1970s with the 3GL run-time libraries having very basic support for their programming languages. Simple math and string manipulation functions primarily. We ended the 1970s with the VAX (nee VMS) Common Run-Time Library offering a rich cross-language set of capabilities, including abstractions for accessing all kinds of services. It was basically the forerunner of what was done in .NET1 in the 2000s.

It wasn’t just languages and run-times we saw changing the landscape. We saw tremenous growth in tooling. Integrated Development Environments (IDE) like Visual Studio started partially generating applications for us, at least providing a template so we didn’t have to start every project with a blank sheet of paper. Rich sample applications appeared. Sites like Experts Exchange and StackOverflow appeared, giving developers access to more examples and code fragments, plus expert advice. Codeplex and then Github, became repositories of all kinds of reusable code. Search engines, particularly Google, became the go to tool for finding code or libraries you could reuse for any project.

In the 2010s no one was writing applications from scratch, they were using 3rd party libraries layered on other 3rd party libraries, and using source code picked up off of Github, to construct their application. Application development was largely a wiring problem. Even traditionally lower level programming moved into this mode. You don’t write a compiler backend, you use LLVM. And you use tools like ANTLR or Flex+Bison to create the compiler front-end.

The broader Information Technology space was also struggling in the 1970s with the “Application Backlog”. As computing grew programmers just couldn’t keep up with application demand. The business people would ask for a new report and be told there was a one year wait before the programming staff could get around to it. Report Writers and query tools like RAMIS, FOCUS, and Datatrieve were created, both to increase programmer productivity but also to give non-programmers a way to meet some of their own application development needs. These were the early 4th Generation Languages. They were followed by an ever increasing flow of Rapid Application Development tools. At DEC in the late 1980s we did TEAMDATA and RALLY2.

4GLs and Rapid Application Development really took off in the PC world. Who can forget Crystal Reports? Microsoft Access became the bane of IT department’s existence as users developed their own apps and, more to IT’s problem, deployed them across organizations! Spreadsheets, and particularly Microsoft Excel, rules the application world. At one point at Microsoft we concluded there was more data stored in Excel spreadsheets than all the data in databases3. Then up until recently NoCode/LowCode, often based off the spreadsheet model, was all the rage.

And then there is “The Web”, and HTML, and JavaScript, and the myriad of tools that were created to make both client and backend website development easy. We even ended up with new categories of developers, Web Developers and Full Stack Developers, as a result. We even have a caste system, with Software Engineers generally deriding Web Developers4.

The funny thing is that despite this enormous effort to make development something anyone could do, thoughout this century we’ve seen an explosion of growth in Software Engineers. It takes a lot of people, with a lot of expertise, to build things for hyperscale. The amount of distributed systems expertise at places like AWS is just staggering. But what those people do is make it so 98% of developers out there can build distributed systems without understanding distributed systems.

Which gets us to the main point of this long blog entry. The main thing that those of us working in the software industry have focused on since the 1950s, with ever accelerating effort, is to eliminate (or at least dramatically reduce) the need for computer programming. We’ve made it so only a tiny fraction of those developing applications actually know how to program a computer. We’ve made it so most can achieve 80% of what they are building using existing libraries, code bases, and services. We’ve made some classes of applications, for example spreadsheets, not seem like programming at all. But in a broad sense we haven’t eliminated programmers. Will Generative AI finally be the tool that eliminates most need for programming? Or, like our other efforts, actually fuel more development just at yet another a higher level of abstraction. In any case, it is hard for me to get bent out of shape over Generative AI replacing classic programming. That’s been our goal all along.

Epilogue: One of the fun things I did when I was still in the early stage of my career was write a lock manager for a database system. I had no formal education. There was no Internet, so no way to easily research. There was no code to model on. So it was a great example to play with Generative AI. I asked Grok to write me a lock manager. Looked good. I asked for some features often mentioned, but rarely used, in lock managers. It added those. I asked it to make it distributed. Then I started asking it to make optimizations. I got excited about what it did. The interesting part was I had to ask for the features and for the optimizations. I still created the lock manager, just at a different level of abstraction. I had to express what I wanted, and do it clearly. Coding a lock manager in the 1970s was fun. Being on the periphery of distributed lock manager development in the 1980s was also fun. Thinking about coding a new one in the 2020s? Boring. I could get excited about creating a new database system, but a lot of the pieces I just want to make happen, not get into the weeds of every individual piece. I’d be happy to let GenAI do that for me.

- In 1994, one of David Vaskevitch’s roles at Microsoft was CTO of Developer Division. As he came out of a DevDiv staff meeting I asked what they had talked about. He described that he was pushing for a common run-time across the languages, and from the description I pointed out that it sounded just like the VAX Common Run-Time. David was later the Sr. VP of DevDiv during development of .NET. ↩︎

- These sadly did not survive DEC’s sale of its database business to Oracle. Datatrieve is actually still alive, maintained and sold by VMS Software Inc. ↩︎

- That was before the “Big Data” era ↩︎

- In the 1960s-70s there was a similar caste system, Application Programmers and System Programmers. ↩︎

Update (1/4): Since some people are misreading this post (not a surprise when 10s of thousands of people have read it) so let me clarify. I’m not picking on developers at any level here. I’m not suggesting that we go back to writing everything (or even anything) in assembler. I’m pointing out that we keep adding abstractions to make it easier for both professional programmers to be more productive AND for those who are not programmers to solve their own problems without requiring the help of a professional programmer. And that’s how we should look at AI. For some of us it is a new tool for helping us write apps. For others, it is a means to not have to write an app directly at all. It is possible this means fewer jobs for professional programmers going forward. More likely it means there is greater demand for analysis and high level design skills, less demand for coding skills. In any case, we need to embrace AI not fight it.